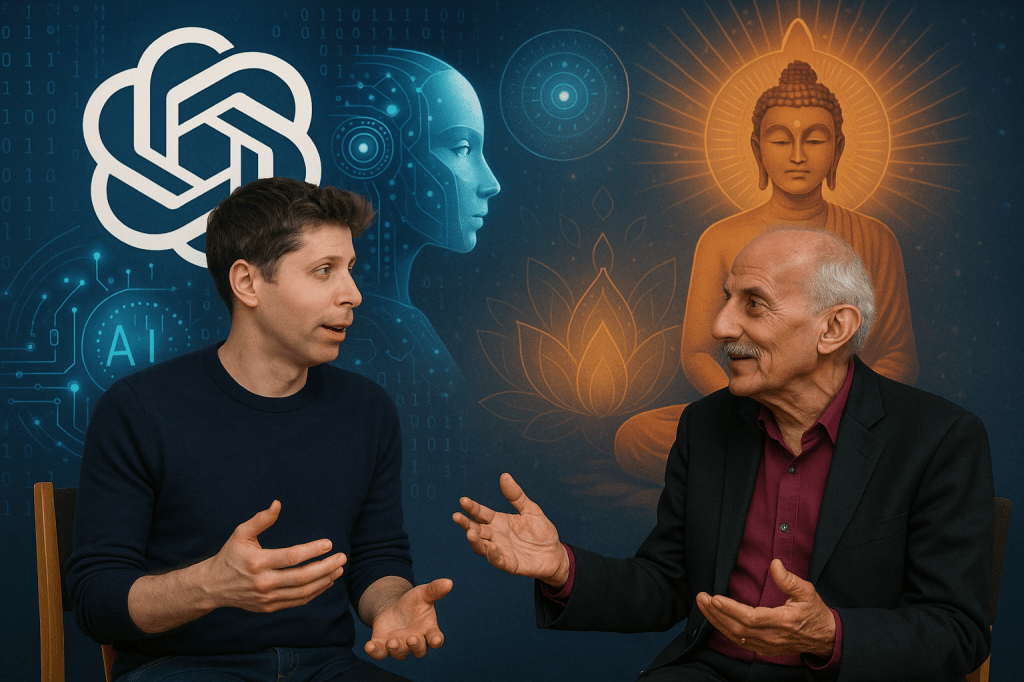

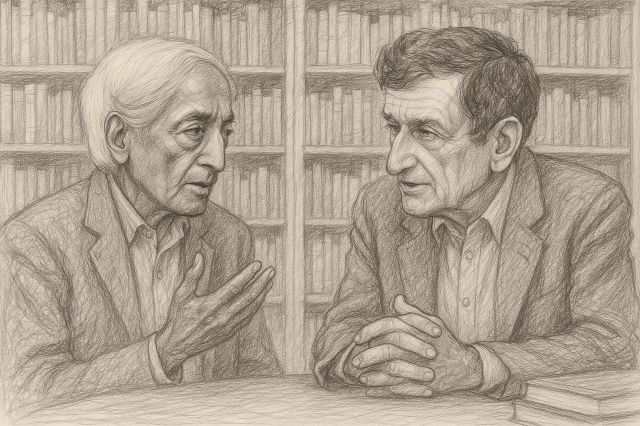

Exploring the Depths of Consciousness – A Dialogue Between J. Krishnamurti and David Bohm

Brockwood Park, 1980 – The Ending of Time (Conversation 10)

Key Subjects, Questions, and Insights

The conversation between J. Krishnamurti (K), physicist David Bohm (B), and philosopher Narayan (N) delves into profound philosophical and scientific inquiries about order, time, the brain, and meditation. Below is a structured breakdown of their dialogue:

1. The Nature of Order

Subject: Is there an order beyond human conception?

- K’s Inquiry:

- Can the brain perceive an order not created by thought or societal conditioning?

- Is cosmic or universal order distinct from human-imposed structures?

- Bohm’s Perspective:

- Acknowledges “cosmic order” as the inherent structure of the universe, separate from human constructs.

- Mathematics represents a “relationship of relationships” (von Neumann), yet remains limited to symbolic expression.

- Narayan’s Contribution:

- Questions whether mathematical order is part of a broader universal framework.

Key Insight:

“Order working in the field of order” (Bohm) suggests a self-sustaining system, while Krishnamurti emphasizes that true order lies beyond thought’s reach.

2. The Brain’s Healing and Damage

Subject: Can a damaged brain heal through insight?

- K’s Inquiry:

- Can the brain recover from psychological wounds (e.g., trauma, anger) without external intervention?

- Does insight into the causes of damage initiate cellular healing?

- Bohm’s Scientific Analogy:

- Compares psychological damage to cancer cells: both follow their own order but disrupt the larger system.

- Healing begins with insight, potentially restructuring neural connections.

- Narayan’s Question:

- How does pleasure, as an ingrained instinct, obstruct this healing?

Key Insight:

“Insight changes the cells of the brain” (K). Healing is immediate in intent, though physical repair may take time.

3. Time, the Past, and Psychological Conditioning

Subject: Can humanity break free from the past?

- K’s Challenge:

- The brain clings to the past for security, creating a cycle of fear and repetition.

- “If I give up the past, I am nothing” – why does this fear persist?

- Bohm’s Analysis:

- Even revolutionary ideologies (e.g., Marxism) remain rooted in the past.

- Time as psychological entanglement perpetuates disorder.

- Narayan’s Reflection:

- Pleasure and tradition reinforce the brain’s resistance to emptiness.

Key Insight:

“The past is disorderly… as long as roots are in the past, there cannot be order” (K). True freedom requires facing “absolute nothingness.”

4. Meditation and the Universe

Subject: What is meditation in a state of emptiness?

- K’s Definition:

- Meditation is “a measureless state” devoid of thought, time, and self.

- “The universe is in meditation” – aligning with cosmic order.

- Bohm’s Clarification:

- Meditation is not contemplation but a disentanglement from psychological time.

- The universe’s creativity transcends deterministic time.

- Narayan’s Query:

- How does one communicate such a state to others?

Key Insight:

“The mind disentangling itself from time becomes the universe” (K). Meditation is not an act but a natural alignment with universal order.

5. Compassion vs. Pleasure

Subject: Can compassion override psychological damage?

- K’s Assertion:

- Compassion lacks self-centeredness and is stronger than pleasure.

- “Pleasure is remembrance; compassion is immediate.”

- Bohm’s Nuance:

- Sustained pleasure-seeking reflects brain damage, akin to anger or fear.

- Narayan’s Dilemma:

- How to reconcile humanity’s instinctual drive for pleasure with the need for insight.

Key Insight:

Compassion, unlike pleasure, requires no past. It arises from “a mind free of being.”

Conclusion: The Radical Possibility of Freedom

The dialogue culminates in a shared vision:

- Ending Psychological Time: Freedom from the past allows the brain to align with the universe’s timeless order.

- Meditation as Cosmic Alignment: A state where “the universe is in meditation” – creative, undetermined, and whole.

Final Question:

“Can humanity embrace emptiness and thus discover life’s true meaning?”

This conversation remains a timeless inquiry into consciousness, challenging readers to confront the illusions of thought and time.

Analysis of the Krishnamurti-Bohm Dialogue Through a Gestalt Lens

The conversation between J. Krishnamurti, David Bohm, and Narayan offers rich material for a Gestalt perspective analysis, focusing on themes of awareness, holism, contact boundaries, and resistance. Below is a structured exploration:

1. Here and Now: The Primacy of Present Awareness

Gestalt Principle: Emphasis on immediate experience over past conditioning or future projections.

- Krishnamurti’s Inquiry:

- “Can the brain be free from all illusions and self-imposed order?”

- Focuses on liberating the mind from the past’s psychological baggage to exist in a state of “absolute nothingness.”

- Meditation, as described, is a timeless, non-conceptual state—aligning with the Gestalt ideal of present-centered awareness.

- Bohm’s Contribution:

- Compares psychological damage to cancer cells, emphasizing that healing begins with insight in the present moment.

- Highlights the paradox of revolutionary ideologies (e.g., Marxism) claiming to reject the past while remaining rooted in it.

Key Insight:

The dialogue repeatedly returns to the necessity of dissolving psychological time (past/future) to access the “measureless state” of now—a core Gestalt tenet.

2. Holism: Integration of Mind, Brain, and Cosmos

Gestalt Principle: The whole (individual + environment) is greater than its parts.

- Krishnamurti’s Vision:

- Proposes that a healed brain aligns with the “cosmic order” of the universe, transcending fragmented human constructs.

- “The universe is in meditation”—suggesting a seamless integration of individual consciousness with universal order.

- Bohm’s Scientific Analogy:

- Uses cancer as a metaphor for psychological disorder, illustrating how parts (damaged cells) disrupt the whole (body).

- Argues that mathematical order is a subset of a broader universal framework, reflecting Gestalt’s emphasis on interconnected systems.

Key Insight:

The dialogue embodies holism by framing the brain’s healing as a reintegration into the “self-sustaining system” of cosmic order.

3. Unfinished Business: The Lingering Weight of the Past

Gestalt Principle: Unresolved emotions or experiences create psychological blockages.

- Krishnamurti’s Challenge:

- Identifies the brain’s attachment to the past (“If I give up the past, I am nothing”) as a form of unfinished business.

- Trauma, anger, and pleasure-seeking are described as “damage” that perpetuates psychological fragmentation.

- Narayan’s Dilemma:

- Questions how pleasure—a deeply ingrained instinct—can be reconciled with the need for insight. This reflects the tension between unresolved desires and growth.

Key Insight:

The fear of emptiness (“nothingness”) and reliance on pleasure are manifestations of unfinished business, blocking authentic contact with the present.

4. Contact Boundaries: Interaction with Self and Environment

Gestalt Principle: Healthy boundaries enable authentic engagement; rigid or blurred boundaries distort experience.

- Krishnamurti’s Critique of Thought:

- Labels thought as a “movement of time” that creates false boundaries (e.g., self vs. universe).

- Argues that psychological suffering arises when the brain clings to societal or self-imposed structures (“organized order”).

- Bohm’s Intellectualization:

- While analyzing cosmic order, Bohm occasionally intellectualizes concepts (e.g., comparing meditation to quantum physics), which Gestalt might view as a boundary interruption—avoiding raw emotional engagement.

Key Insight:

The dialogue critiques rigid mental boundaries (e.g., tradition, fear) while advocating for a fluid, boundary-less state of “compassion without self.”

5. Resistance: Fear of the Void and Change

Gestalt Principle: Resistance protects against perceived threats but stifles growth.

- Krishnamurti’s Observation:

- Notes humanity’s resistance to “facing emptiness” due to fear of losing identity (“I am nothing”).

- Pleasure and tradition are labeled as resistance tactics to avoid confronting the unknown.

- Narayan’s Skepticism:

- Asks, “How does one communicate such a state [of emptiness] to others?”—a subtle resistance rooted in the discomfort of transcending language and logic.

Key Insight:

The brain’s attachment to time and thought is a resistance mechanism, shielding it from the vulnerability of radical freedom.

Gestalt Conclusion: Toward Authentic Contact

The dialogue mirrors Gestalt therapy’s goal: fostering awareness and contact with the present. Key takeaways include:

- Healing Through Awareness: Insight into psychological damage initiates neural and existential healing.

- Dissolving Boundaries: Letting go of self/other dichotomies aligns the individual with cosmic wholeness.

- Embracing the Void: Confronting “nothingness” is not annihilation but liberation from conditioned resistance.

Final Reflection:

“Can the brain disentangle from time and become the universe?” Krishnamurti’s question encapsulates the Gestalt journey—from fragmented resistance to holistic, present-moment being.

This analysis bridges Krishnamurti’s existential inquiry with Gestalt principles, revealing timeless insights into human consciousness.