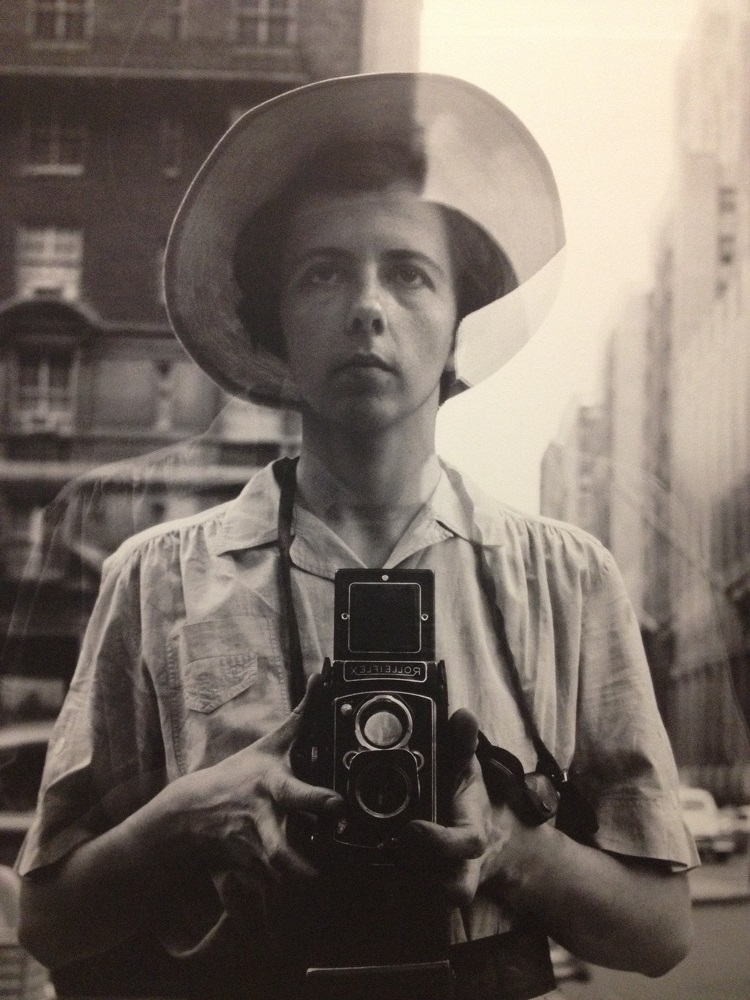

Image by kikasworld / Vivian Maier exhibition 2014 Foam Amsterdam

Introduction

“To be is to be in relation,” the Gestalt therapist might say—not merely as a poetic phrase but as a fundamental principle of existence. We are not entities floating in abstract isolation, but processes, always becoming, always shaped and reshaped by the field of relationships in which we dwell. This blog explores the deep and intricate question:

Can we truly exist without relationship?

What does it mean to observe oneself in relationship, and how does this observation influence the way we perceive ourselves, others, and the world? Drawing on Gestalt therapy, existential philosophy, and insights from thinkers like J. Krishnamurti, we will delve into the interiority of human experience and the unfolding of the self in the tapestry of interbeing.

I. The Gestalt Perspective: Relationship as Ground of Being

Gestalt therapy, developed by Fritz Perls, Laura Perls, and Paul Goodman, places the emphasis not on what we are, but how we are. It eschews the fixed, static notion of self in favor of a dynamic, moment-to-moment awareness of experience. Central to this is the concept of contact—the boundary at which self and other meet, where awareness emerges and where change becomes possible.

In Gestalt therapy, the self is not a thing, but a process: the ongoing, emergent function of boundary regulation between organism and environment. We are only ourselves in contact. Thus, to observe oneself is not to look inward in isolation, but to become aware of how we are in relationship—with others, with the world, with time, with our own thoughts and emotions.

“Awareness in itself is healing.” — Fritz Perls

To observe thyself in relationship, then, is to become conscious of how we respond, avoid, connect, project, and withdraw. Are we leaning into a situation? Avoiding conflict? Seeking approval? Manipulating the moment? All these are relational strategies, patterns of behavior that shape the contours of who we appear to be.

II. When Do We Exist? The Now as Relational Event

From a Gestalt perspective, we exist in the present moment—not as an isolated unit of time, but as the site of contact. The now is where potential is actualized. The past becomes relevant only as it is re-experienced in the present; the future matters only in how it is anticipated now.

Consider a person sitting silently across from a stranger in a café. On the surface, there is no contact. But inwardly, there may be stories forming, projections happening, curiosity arising. Perhaps we feel discomfort, a pull to make eye contact, a resistance to being seen. All of this is relationship. The stranger becomes a mirror, a screen, a catalyst.

In this sense, even in solitude, we are in relationship—with memories, fantasies, expectations, fears, and ideals. We exist in how we relate to these inward phenomena. The Gestalt therapist invites us to bring these dynamics to awareness, not to fix them, but to inhabit them more fully.

III. The Danger of Abstraction: Can We Exist Outside Relationship?

Krishnamurti, the Indian philosopher who spent his life inviting people to see clearly, often emphasized the problem of abstraction. When we live in concepts—of the self, the other, success, love, morality—we cease to be in direct contact with what is.

“The word is not the thing. The description is not the described.” — J. Krishnamurti

To abstract is to step away from experience. It is to reduce the richness of relationship to a label, to a story, to a belief. In Gestalt terms, abstraction is a form of withdrawal, a retreat from the immediacy of contact.

Can we exist in abstraction? Only as an idea. But not as living, breathing, aware beings. To truly exist is to engage, to sense, to feel, to meet the world freshly, not through the veil of preconception. Abstraction can help us understand systems, patterns, and ideas—but it cannot substitute for the direct experience of being.

IV. Observing the Observer: Who is Watching?

The act of observing oneself raises a profound question: who is the observer? In Gestalt therapy, we often work with the awareness continuum, a process of noticing what is figural (in the foreground) and what is ground (background) in our awareness. We observe thoughts, sensations, emotions, behaviors—but we do not fixate on a permanent ‘self’ behind the observation.

Krishnamurti again offers insight: “The observer is the observed.” This radical statement dismantles the illusion of duality. The mind that judges is not separate from what it judges. Our anger, when observed, is not apart from us—it is us. There is no pure vantage point from which to analyze oneself objectively. Observation becomes an act of integration, not separation.

In Gestalt terms, this aligns with the principle of wholeness. We cannot split ourselves into subject and object without losing the unity of the moment. To observe thyself in relationship is to acknowledge that every observation is itself part of a larger relational field—shaped by context, history, emotion, and desire.

V. The Paradox of the Self in Dialogue

Martin Buber, in I and Thou, writes that true relationship happens not between I and It (objectification) but I and Thou (presence). This echoes through Gestalt therapy, where presence, authenticity, and dialogue are core elements. In a therapeutic setting, the client and therapist meet not as roles, but as co-creators of meaning.

In daily life, we are constantly in such dialogues—with others and with ourselves. The self is not a solitary monologue but a polyphonic chorus of voices, many internalized from past relationships: the critical parent, the nurturing friend, the shamed child. When we observe ourselves, we often encounter these voices. Can we listen to them with compassion? Can we respond rather than react?

To be in dialogue is to allow for mutual transformation. The self is not fixed; it unfolds in the space between. We become who we are through the quality of our encounters. Every relationship is an invitation to become more whole.

VI. The Body as Ground: Relationship Through Sensation

Gestalt therapy insists that awareness begins in the body. Sensation is the most direct mode of knowing. Before we name our emotions or tell stories about them, they are felt in the gut, the chest, the skin.

To observe oneself in relationship is to sense how the body responds: the tightening of the jaw when a certain person enters the room; the warm expansion of the chest when a friend smiles; the subtle contraction when we tell a half-truth. These are not just private phenomena—they are signals of contact, indicators of relational truth.

Too often, we override the body with thought. Yet the body does not lie. It anchors us in the here and now. It reveals the truth of relationship before the mind can interfere.

VII. The Field Perspective: We Are Not Alone

Gestalt therapy speaks of the field—the total situation in which we exist. We are not isolated islands, but participants in a shared field that includes environment, history, culture, and social norms.

Observing thyself in relationship means understanding that our responses are co-created by the field. My anger may arise not just from personal history, but from systemic injustice. My joy may be amplified by cultural permission to celebrate. The self is shaped not only in intimate relationships but in the wider societal matrix.

This invites humility. What we observe in ourselves is not only ours. It belongs to the collective. To heal individually is to contribute to the healing of the field.

VIII. Living the Question: A Reflective Practice

To conclude, let us not rush to answers. The value of observing oneself in relationship lies in living the question. As Rainer Maria Rilke once advised: “Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves.”

- What does it mean to truly meet another?

- How do I defend against contact?

- Where do I project, and what do I fear to own?

- How does my body speak my relational truth?

- What patterns do I repeat, and what do they reveal?

These are not problems to be solved, but doorways into deeper presence. Through Gestalt practice, contemplative inquiry, and honest encounter, we can begin to see ourselves not as isolated entities, but as living relationships—fluid, open, evolving.

In observing thyself in relationship, perhaps we find that existence itself is not a noun, but a verb. Not a fixed identity, but a dance of becoming. Not a solitary fact, but a shared unfolding.

Further Reading and Exploration

- “Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality” by Perls, Hefferline, and Goodman

- “The Art of Listening” by Erich Fromm

- “Freedom from the Known” by J. Krishnamurti

- “I and Thou” by Martin Buber

- “The Courage to Be” by Paul Tillich