(Image created by chatGPT)

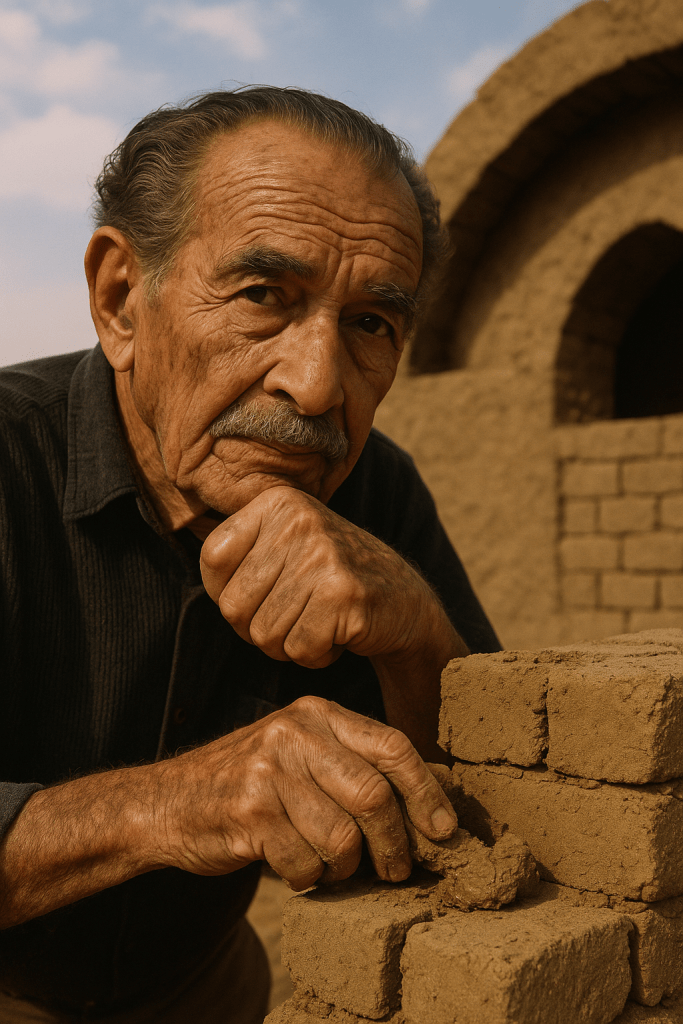

When we think of Egyptian architecture, our minds often leap to the grandeur of the pyramids, temples, or the mysteries of Imhotep. Yet, in the 20th century, another name emerged as a beacon of vision and humility: Hassan Fathy (1900–1989). Unlike the monumental builders of ancient Egypt, Fathy’s mission was not to glorify kings or gods, but to serve the ordinary people of his country.

A Life of Contrasts

Born into an affluent, aristocratic family in Alexandria, Fathy could easily have pursued a comfortable life, designing villas and palaces for the wealthy. Instead, he chose a different path. His heart belonged to the poor Egyptian farmers and villagers, those who had little voice and even fewer resources. Despite his elegant dress and refined upbringing, he dedicated his architecture to those who could not afford architects at all.

This choice shaped his legacy. As he once expressed, he preferred to call his work building with the people rather than for the poor—because he believed in dignity, participation, and community, not charity.

Vision and Philosophy

Fathy rejected the industrialized, imported materials of modernist architecture—steel, glass, and concrete—arguing they were unsuited to Egypt’s climate, economy, and traditions. Instead, he turned to the earth itself. “Build your architecture from what is beneath your feet,” he advised, advocating adobe and mudbrick as natural, sustainable materials that had served Egypt for millennia.

For him, architecture was not about spectacle, but about harmony—with nature, with culture, and with human needs. He often said: “If the architect does not respect the God-made environment, it will be a sin against God.” Courtyards for shade, domes and vaults for cooling, and narrow streets for community life were not just design choices, but echoes of wisdom embedded in Egypt’s vernacular traditions.

A Man of Many Talents

Fathy was not only an architect. He was also a professor, engineer, amateur musician, dramatist, and inventor. He designed nearly 160 projects, from modest country retreats to fully planned communities with schools, mosques, markets, and theaters. He trained villagers to make their own building materials and believed strongly in self-reliance. His belief was simple: architecture should be human-scaled, ecological, and empowering.

Projects That Spoke of Hope

One of his earliest commissions after graduating in 1926 was a school in Tala, a small town on the Nile. There, he witnessed appalling poverty, dilapidated houses, and poor sanitation. The experience haunted him and became the seed of his lifelong mission: to improve the lives of those most in need.

His most famous work was the village of New Gourna, near Luxor. Commissioned in the 1940s to resettle communities living near the Valley of the Kings, Fathy envisioned a self-sufficient settlement of homes, mosques, schools, theaters, and markets—all built with local materials by the people themselves. He consulted families, involved ethnographers, and designed spaces that were functional, affordable, and beautiful. He even insisted: “Architecture is for life, not for luxury.”

Successes and Challenges

New Gourna, while visionary, also revealed the tensions between ideals and reality. Many villagers resisted relocation because it cut them off from their livelihoods near archaeological sites. Critics argued that domes and vaults—central to Fathy’s designs—were associated with funerary architecture, and thus culturally inappropriate for homes. Others pointed out that mudbrick, while ecological, required constant upkeep, which some communities struggled to maintain. These criticisms did not erase the brilliance of the project but highlighted the complexities of blending tradition, modern needs, and social change.

Later, he expanded his vision beyond Egypt. In Dar al-Islam, New Mexico (1981), he recreated adobe-based community design for a new cultural and educational center. In New Baris village, deep in the Egyptian desert, he created an austere yet noble settlement for families. He also built houses in Jordan and designed apartments in Cairo that blended tradition with modern comfort. Even in exile, his buildings radiated warmth and dignity.

Renderings Full of Life

Fathy’s architectural drawings themselves were works of art. Unlike the cold precision of modern renderings, his sketches were full of imagination—birds flying across facades, trees drawn horizontally, animals and people living within the plans. To him, drawings were not about rigid objectivity but about evoking life. He once remarked: “Architecture must leave space for imagination, because imagination gives freedom.”

Recognition and Legacy

In 1980, he was honored with the Aga Khan Chairman’s Award for Architecture. In 2017, Google celebrated him with a Google Doodle, acknowledging his pioneering contributions. Yet, despite the recognition, he remained a modest visionary. “It is not luxury people need—it is water, shade, and dignity,” he reminded the world.

Hassan Fathy has often been called the father of sustainable architecture in the Middle East. His ideas—about passive cooling, natural materials, self-building, and architecture rooted in culture—were decades ahead of their time. In an era of climate crisis and social inequality, his work feels more urgent than ever.

The Timeless Voice of Hassan Fathy

Perhaps his own words express his philosophy best:

- “We are nothing like poor and rich—we are all human beings.”

- “When man builds with his own hands, he leaves something of himself in the building.”

- “Beauty exists in nature when form conciliates the forces acting on it. Architecture must learn from this harmony.”

Hassan Fathy did not build monuments to power or ego. He built homes, villages, and communities. He built with mud, but also with imagination, compassion, and faith. More than buildings, he left us an invitation: to rediscover architecture as an act of respect—for people, for culture, and for the Earth itself.

REFERENCES:

HASSAN FATHY | born today / International Celebrations in Architecture