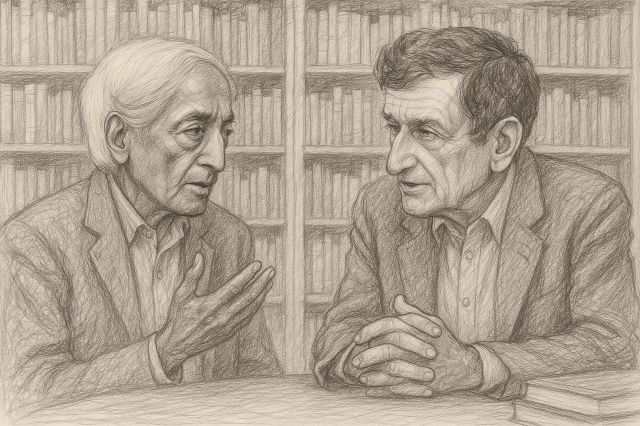

In their profound 1980 dialogue, philosopher J. Krishnamurti and physicist David Bohm delved into the psychological roots of human conflict, the role of time, and the nature of consciousness. Below is an analysis of their exchange, highlighting key questions and answers that shaped their exploration.

1. The Wrong Turn of Humanity

Krishnamurti: “Sir, how shall we start this? … Has humanity taken a wrong turn?”

Bohm: “A wrong turn? Well, it must have done so, a long time ago, I think.”

Krishnamurti posits that humanity’s psychological suffering stems from a historical misdirection—prioritizing exploitation over constructive growth. Bohm traces this to ancient practices like slavery, where external conquest replaced inward understanding.

Krishnamurti: “What is the root of conflict, not only outwardly, but also this tremendous inward conflict of humanity?”

Bohm: “It seems it would be contradictory desires.”

Krishnamurti: “No. Is it that we are all trying to become something?”

Here, Krishnamurti challenges the notion of desire as the root, instead pointing to the drive for psychological “becoming”—a perpetual effort to transcend the present self.

2. Time and the Ego

Krishnamurti: “Is time the factor? … Time, becoming, which implies time.”

Bohm: “Time applied outwardly causes no difficulty. … But inwardly, the idea of time.”

They agree that while time is practical for external tasks (e.g., learning a skill), its inward application creates division. The ego (“I”) emerges from this division, perpetuating conflict between “what is” and “what should be.”

Krishnamurti: “Why has mankind created this ‘I’?”

Bohm: “Having introduced separation outwardly, we then kept on doing it inwardly. … Not seeing what they are doing.”

Bohm attributes the ego to an unconscious extension of external hierarchies into the psyche.

3. The Brain, Energy, and Evolution

Krishnamurti: “Could we say the brain cannot hold this vast energy?”

Bohm: “The brain feels it can’t control something inside, so it establishes order.”

Krishnamurti suggests the brain’s limitation in channeling boundless energy leads to the ego’s narrow construct. Bohm adds that the brain, conditioned by evolution, defaults to time-bound solutions.

Krishnamurti: “I want to question evolution. … Psychologically, to me, that is the enemy.”

Bohm: “You may question whether mentally evolution has any meaning.”

While acknowledging physical evolution, Krishnamurti rejects psychological evolution, arguing it traps humanity in time.

4. Ending Psychological Time

Krishnamurti: “If there is no inward movement as time, what takes place?”

Bohm: “The mind operates without time. … The brain, dominated by time, cannot respond properly to mind.”

They propose ending psychological time dissolves the ego, allowing the brain to align with the timeless mind.

Krishnamurti: “How is one to say, ‘This way leads to peace’?”

Bohm: “The whole structure of time collapses. … There is another kind of thought not dominated by time.”

Bohm emphasizes that transcending time requires rejecting all methods, as methods themselves imply time.

5. The Source of Energy and “Nothingness”

Krishnamurti: “What is there without psychological knowledge?”

Bohm: “Energy is what is. … No need for a source.”

Krishnamurti describes a meditative state where the “source of all energy” is realized—a “nothingness” that paradoxically contains everything.

Krishnamurti: “Is this the end of the journey?”

Bohm: “It might be the beginning. … A movement with no time.”

They conclude that ending time is not stagnation but a timeless beginning, where energy and existence merge.

6. The Role of Meditation

While Krishnamurti speaks poetically of “waking up meditating,” Bohm provides a conceptual scaffold:

- Krishnamurti: Meditation is a spontaneous, egoless state.

- Bohm: Meditation is the brain’s capacity to “see its own conditioning” and operate beyond time, enabling coherence between mind and matter.

For Bohm, meditation is not a practice but a profound reordering of perception—a shift from fragmented, time-bound thought to a holistic awareness of the “unbroken wholeness” of existence. It is the mind’s ability to “observe without the observer,” dissolving the ego’s illusion and aligning with the timeless flow of energy. In his words:

“When the movement of time ceases, there is a beginning—not in time, but of creativity itself.”

This perspective bridges science and spirituality, framing meditation as both a psychological liberation and a cosmic alignment with the fundamental nature of reality.

Conclusion

Krishnamurti and Bohm’s dialogue challenges humanity to abandon psychological time and the ego’s illusion. Their insights reveal that conflict arises from the separation of “I” and “not I,” perpetuated by inward time. By ending this division, one accesses a boundless energy—where “nothing” is the fullness of existence. As Krishnamurti states, “The ending is a beginning.”

This conversation remains a timeless inquiry into consciousness, urging a radical reorientation from becoming to being.

Integrating the Dialogue with the Gestalt Perspective: Similarities and Divergences

The dialogue between Krishnamurti and Bohm explores timeless themes of psychological conflict, ego dissolution, and the transcendence of time. When viewed through the lens of Gestalt psychology and therapy, these ideas resonate deeply while also diverging in methodology and emphasis. Below is an analysis of their intersections and distinctions:

Similarities

- Emphasis on the Present Moment

- Krishnamurti & Bohm: Stress ending psychological time to resolve conflict. Krishnamurti asserts, “To abolish time psychologically is to end the ‘I’ and its conflicts.”

- Gestalt Perspective: Prioritizes the “here and now,” urging individuals to fully experience the present. Fritz Perls, founder of Gestalt therapy, famously stated, “Nothing exists except the now.” Both frameworks reject dwelling on past regrets or future anxieties.

- Holistic Perception

- Krishnamurti & Bohm: Describe the ego as a fragmented construct that distorts the “whole” of energy. Ending this fragmentation aligns with accessing a unified state of being.

- Gestalt Perspective: Emphasizes the law of Prägnanz (the mind’s tendency to perceive wholes). In therapy, this translates to integrating fragmented parts of the self (e.g., repressed emotions) into a cohesive whole.

- Unfinished Business vs. Psychological Time

- Krishnamurti & Bohm: Identify clinging to time as a source of conflict (e.g., “becoming” traps the mind in perpetual dissatisfaction).

- Gestalt Perspective: Attributes suffering to unfinished business—unresolved emotions or experiences that keep individuals psychologically stuck. Both frameworks highlight the need to resolve past patterns to achieve liberation.

- Awareness as Liberation

- Krishnamurti: Advocates “observation without the observer,” akin to Gestalt’s awareness continuum, where nonjudgmental attention to present experience dissolves mental barriers.

- Gestalt Therapy: Uses techniques like the empty chair dialogue to bring unconscious conflicts into conscious awareness, mirroring Krishnamurti’s call to “face the fact and end it immediately.”

Divergences

- Approach to the Self

- Krishnamurti & Bohm: Propose transcending the self entirely (e.g., “When there is no ‘I,’ there is no conflict”).

- Gestalt Perspective: Focuses on integrating parts of the self (e.g., reconciling the “top dog” and “underdog” roles) to create a healthier, whole identity. Gestalt works within the self’s structure, while Krishnamurti seeks to dissolve it.

- Role of Time and Methods

- Krishnamurti & Bohm: Reject all methods (e.g., “Every method implies time”) and conceptual frameworks as perpetuating psychological time.

- Gestalt Perspective: Employs structured techniques (e.g., role-playing, body awareness) to facilitate present-moment healing. While Gestalt values immediacy, it accepts pragmatic tools to achieve awareness.

- Concept of Energy

- Krishnamurti & Bohm: Describe energy as a boundless, impersonal force (“nothingness is everything”).

- Gestalt Perspective: Views energy as organism-environment interaction—a dynamic flow shaped by needs (e.g., hunger, belonging). Energy is contextual and relational, not transcendent.

- The Brain vs. the Whole Organism

- Krishnamurti & Bohm: Attribute conflict to the brain’s limitation in handling infinite energy, leading to egoic narrowing.

- Gestalt Perspective: Locates dysfunction in interruptions to contact (e.g., avoidance, projection) between the organism and its environment. Healing occurs through restoring natural contact cycles.

Synthesis: A Unified View of Consciousness

While Krishnamurti and Bohm advocate a radical transcendence of the self and time, Gestalt offers a pragmatic path to wholeness through experiential integration. Together, they illuminate complementary truths:

- Gestalt provides tools to heal the fragmented self in the present.

- Krishnamurti/Bohm point to a transcendent reality beyond the self, where psychological time ceases.

Both frameworks ultimately urge individuals to move beyond mental constructs—whether through dissolving the ego (Krishnamurti) or integrating its parts (Gestalt)—to access a liberated state of being. As Krishnamurti notes, “The ending is a beginning,” echoing Gestalt’s belief that resolution in the present opens new possibilities.