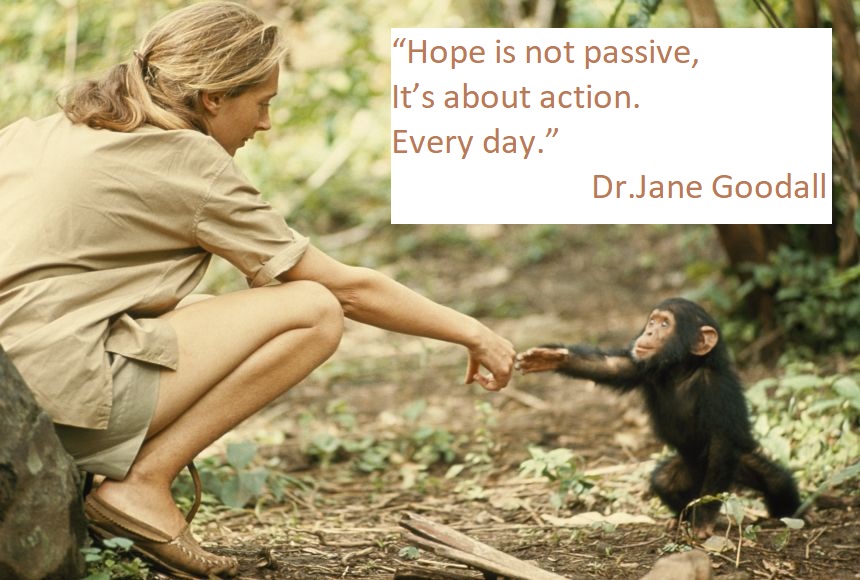

*** Photography by Hugo Van Lawick/National Geographic Creative

In an era marked by accelerating ecological collapse and digital transformation, what does it mean to stay hopeful?

Dr. Jane Goodall—scientist, storyteller, and spiritual matriarch of the natural world—answers this not with rhetoric, but with experience. In a wide-ranging and intimate conversation with Possible host Reid Hoffman, she explores how artificial intelligence, conservation science, youth activism, and moral imagination might all converge into a future that is both survivable and just.

“We’re at a crossroads,” she says. “If we lose hope, we become apathetic. And if we do nothing, we’re doomed.”

But Goodall doesn’t dwell in despair. Instead, she offers something far more subversive in its simplicity: the insistence that hope is a discipline, rooted in daily choices, community, and deep listening.

From Notebooks to Neural Nets: A Conservationist’s Technological Journey

When Goodall first entered the Tanzanian forest in 1960, television had not yet arrived in most homes. Her fieldwork began with handwritten notes and hours of silent observation. Over the decades, that intimate attentiveness merged with technological tools—satellite imagery, drones, camera traps, and most recently, AI-assisted acoustic arrays.

These innovations transformed her field, allowing scientists not just to track animal migrations or map deforestation, but to do the near-impossible: hear species that had never before been identified. One such marvel? The recent discovery of Thomas’s Dwarf Galago, a new species of bush baby, whose calls were picked up in Gombe National Park by AI-enhanced sound sensors.

“It was just a sound we didn’t recognize,” she says. “But it was clearly something new.”

More than gadgetry, these tools democratize data. Local forest monitors—trained in using smartphones and GPS—are now empowered to collect and analyze their own environmental information. Village leaders, once excluded from scientific narratives, are now decision-makers using satellite maps to designate conservation zones.

The Ethical Tension of AI: Helper or Harm?

Despite her awe at the possibilities, Goodall remains cautious about AI’s reach.

“In the wrong hands, it can do real harm—to individuals, to communities,” she warns. “But in the right hands, it’s a powerful tool.”

She envisions AI not as a replacement for human wisdom, but as an amplifier of it. For instance: could AI help scientists decipher patterns in animal communication? Could it create visualizations that help communities see the environmental stakes of their choices? Could it humanize the inhumane by exposing animal abusers to the suffering they cause?

Goodall’s son, a passionate AI advocate, has encouraged her to think more expansively.

“If AI could bring together all the different strands of research—biology, climate science, animal behavior—and show how everything is interlinked,” she muses, “then maybe more people would understand how delicate and interconnected life is.”

She dreams of a tool that makes complexity visible—not just to policymakers, but to the people on the ground: farmers, fishermen, teenagers, activists. A kind of “magic AI” that helps communities not only understand their impact but imagine alternative, sustainable futures.

What We Miss When We Dismiss Anecdotes

Goodall also offered a powerful critique of traditional Western science’s allergy to anecdote.

“I was told when I got to Cambridge that if you observe something only once or twice, it’s not important. But I disagreed completely.”

She recounts a formative moment: a chimp, still wary of humans, hesitates to grab a banana she offers. Instead, it shakes a stalk of grass. When the grass brushes the fruit, the chimp seems to grasp the principle of contact—and soon, using a stick, knocks the banana from her hand.

“That was an insight into his mind,” she says. “It was an ‘aha’ moment—about how he thinks, how he adapts. That’s not something you get from metrics. That’s intelligence.”

She argues that rare behaviors—the stories often discarded as anomalies—are in fact windows into consciousness, both animal and human. And she challenges AI developers to learn from this: to build systems that don’t just measure the repeatable but can also recognize the remarkable.

Roots & Shoots: Hope with Muddy Hands

At the heart of Goodall’s current work is her global youth program, Roots & Shoots, founded in 1991 and now active in 75 countries. From kindergartners to university students, young people design their own community projects—restoring habitats, reducing plastic waste, promoting empathy among species and cultures.

“The main message is: every one of us makes an impact on the planet every day,” she says. “We get to choose what kind of impact.”

She rejects the common refrain “think globally, act locally.”

“That’s backwards,” she says. “If you start by thinking globally, you’ll be overwhelmed and depressed. Instead, ask: what can I change in my community? Do that, and the hope will grow.”

The program’s alumni now include government ministers, educators, and community leaders—individuals carrying forward a vision of environmental justice rooted in compassion and agency.

Facing Crisis Without Losing Faith

The conversation also touches on a painful recent loss: a $5.5 million annual funding cut due to the shutdown of a USAID program. The money once supported local health clinics, girls’ scholarships, and microfinance initiatives—community work central to conservation’s long-term success.

“We’re not closing,” she insists. “Private sector partners are stepping up. We’ll find a way.”

Even here, she refuses to cede ground to despair. Goodall’s hope is not the kind offered in inspirational quotes. It’s the hope that refuses to die, even when facing bureaucratic indifference, ecological collapse, or political regression.

“I’m obstinate,” she says with a smile. “I won’t let other people push me down. I’ll jump up again.”

A Final Word on Sentience

The most existential moment in the conversation comes when Goodall turns the table on Hoffman.

“Could AI ever be sentient?” she asks. “Could it feel?”

The question, Hoffman explains, may be less about replicating human sentience than about discovering new forms of it—through observing both machines and animals.

“We’re going to learn there isn’t one kind of intelligence, one kind of consciousness,” he says. “There’s a whole ecosystem of ways of being.”

Goodall nods—but adds, gently, that some mystery should remain.

“We’re all different. Yet we’re all connected. We’re all sentient. But maybe not everything should be translated. Maybe there’s value in leaving some space for wonder.”

What Kind of Impact Will You Make Today?

Dr. Jane Goodall doesn’t preach. She invites.

She invites us to listen—to animals, to children, to cultures not our own. She invites us to reimagine AI not as an alien threat but as a mirror, a tool that reflects and amplifies our deepest intentions—good or ill.

And most of all, she invites us to choose: to recognize that even small acts—turning off a light, planting a tree, mentoring a young person—echo into larger systems of meaning and change.

“Hope is not passive,” she says. “It’s about action. Every day.”

So in this moment of intersecting crises, when despair feels easy and cynicism seems wise: what will you choose?

What kind of impact will you make today?