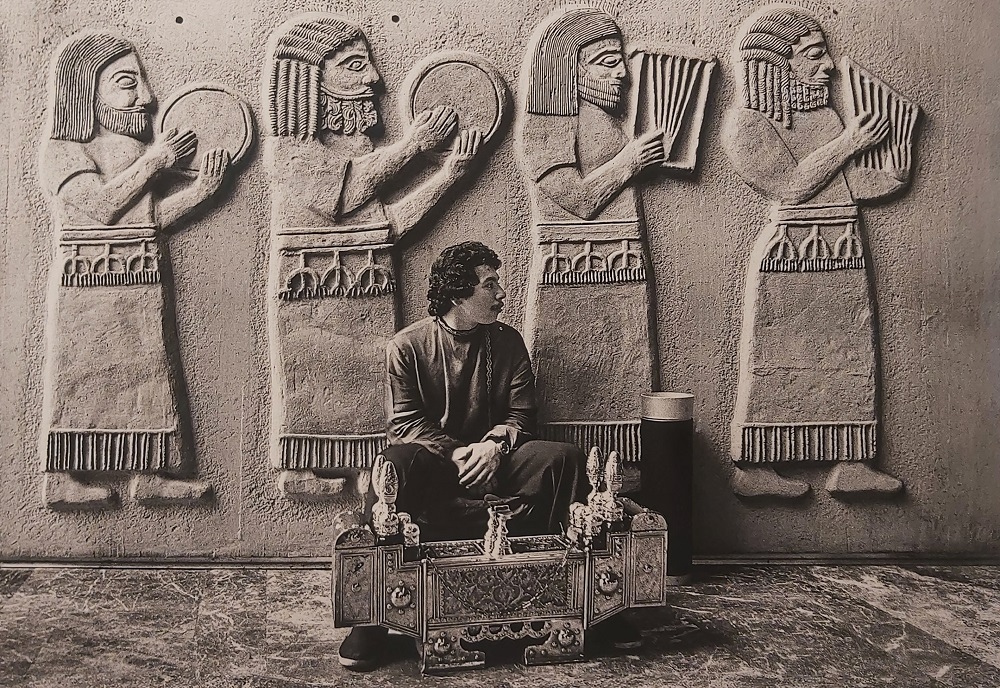

Image: created by AI – does not represent Mr.Karim.

In an era defined by climate crises and technological overload, Dr. Ibrahim Karim, an Egyptian-Swiss architect and founder of BioGeometry, proposes a radical solution rooted in ancient wisdom: harnessing the invisible, harmonizing power of life force energy through geometric design. In a recent interview, Dr. Karim unveiled how this emerging science bridges millennia-old principles with modern innovation to address today’s environmental and health challenges.

The Science of BioGeometry: Harmonizing Energy Through Shape

BioGeometry, a term coined by Dr. Karim, merges “bio” (life) with “geometry” to describe a design language that interacts with life force—an intelligent, holistic energy he believes underpins all natural systems. “Life force is the cradle of creation,” he explains, arguing that modern science’s dismissal of this energy has led to harmful technologies, from electromagnetic radiation to polluting emissions.

Key to BioGeometry is the concept of resonance. By crafting specific geometric shapes—often inspired by nature or ancient sacred sites—Dr. Karim claims these designs can neutralize harmful energies and amplify beneficial ones. For example, small geometric emitters placed in cars or homes purportedly transform electromagnetic fields into “healing cocoons,” akin to Earth’s natural magnetic fields.

From Swiss Valleys to Smart Cities: Proof in Practice

Dr. Karim’s most striking evidence comes from Switzerland, where BioGeometry solutions were applied in regions plagued by health and environmental crises. In the towns of Hemberg and Fischburg, his team reported a 60% reduction in health symptoms—verified by Swiss Parliament doctors—after installing geometric emitters. Migratory birds returned, cows regained fertility, and chronic ailments like headaches and fatigue diminished.

“The government called it the miracle of Hemberg,” Dr. Karim recalls. The solution? Three geometric shapes affixed to mobile communication towers, piggybacking on signals to distribute harmonized energy across the region.

Ancient Civilizations and the Lost Art of Life Force

Dr. Karim draws parallels between BioGeometry and ancient practices. Sacred sites like Egypt’s pyramids or European cathedrals, he argues, were strategically built atop underground water veins and energy grid intersections. These “power spots” emitted life force, fostering health and societal cohesion. “History is the history of power spots” he asserts, lamenting modern cities’ disconnect from these natural grids.

He criticizes theories that ancient Egyptians used pyramids for electricity, insisting their true purpose was life force amplification. “They planted their architecture in nature,” he says, likening ancient structures to living organisms.

A Crossroads for Humanity

Dr. Karim warns that without integrating life force into modern tech, civilization risks collapse. Yet he remains optimistic: BioGeometry’s applications—from wearable “bio-signature” pendants to city planning—could revolutionize industries. His BioSignatures App, launching soon, allows users to print and apply geometric designs for personal energy harmonization.

The Physics of Quality: A New Frontier

Central to Dr. Karim’s work is the “physics of quality,” a framework exploring the 98% of reality beyond sensory perception. He likens life force to a “hidden orchestra” governing biological functions, accessible through resonance. “Your body is run by the universe,” he says, urging a shift from quantitative to qualitative science.

A Call to Reconnect

As climate disasters escalate, Dr. Karim’s message resonates: humanity must realign with Earth’s life force or face expulsion from its “immune system.” His vision? A future where technology and nature coexist through BioGeometry’s principles. “We are cells in Earth’s body,” he concludes. “To survive, we must harmonize—not dominate.”

Dr. Ibrahim Karim’s books, including Hidden Reality: The Physics of Quality and BioGeometry Signatures, are available online. Learn more at https://www.biogeometry.ca/home

This article synthesizes key insights from Dr. Karim’s interview, emphasizing actionable solutions and historical context. For the full discussion, visit YouTube.